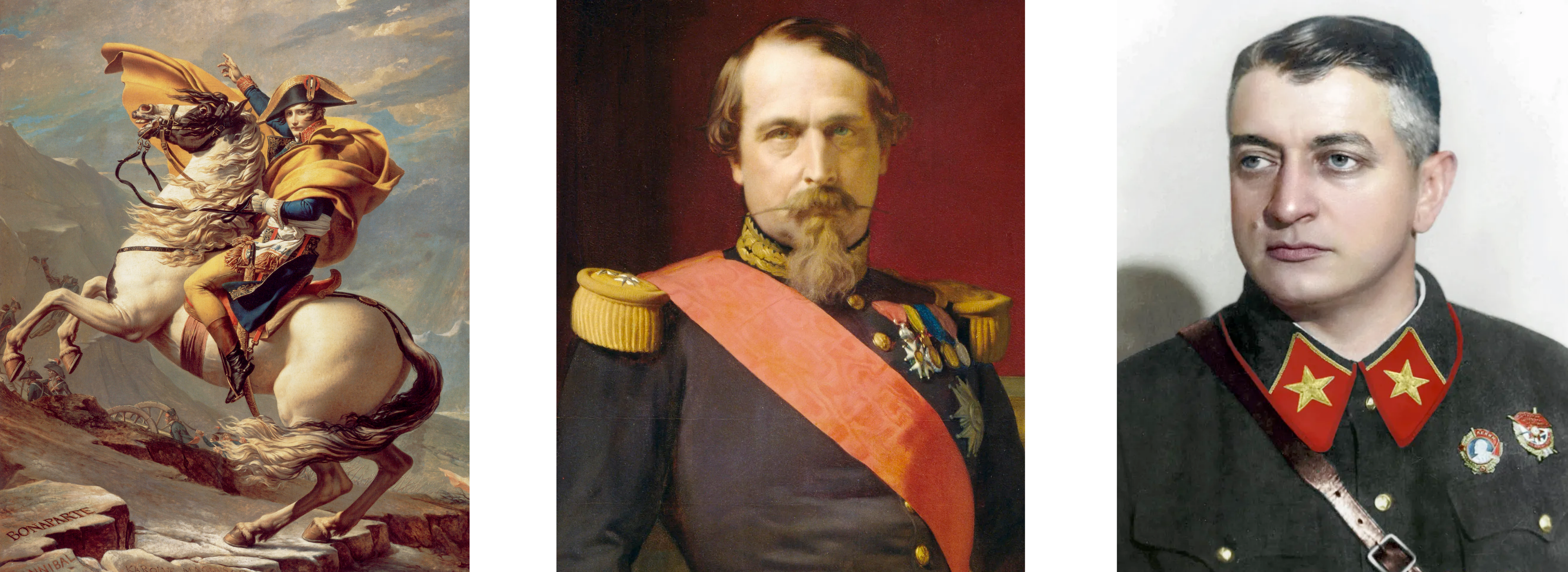

Reflections on Bonapartism

A young Napoleon is certain he will rule France.

He studies military history obsessively. Writes treatises on artillery, on governance. He understands that history has a shape, and he is part of it. The feeling isn’t ambition. It’s quieter. A fact about the world he hasn’t yet proven.

At 28, he launches his first coup. It fails. At 32, he tries again. Failure, prison, escape, exile. He wanders Europe writing political philosophy. He waits.

At 40, he finally becomes Emperor.

And then he proves the feeling had lied. He stumbles into a catastrophic war with Prussia. His army is encircled at Sedan. He surrenders personally to Bismarck. He is deposed. He dies in exile three years later.

This was Napoleon III. The nephew. The farce.

His uncle had the same feeling. The difference is his uncle was right.

The Feeling

What do you do with a conviction you can’t verify?

Some people carry it from childhood. A sense of being meant for something. Not arrogance, but quieter. More like a fact about the world that happens to involve you. You don’t choose it. It’s just there, the way some people are left-handed.

Napoleon I had it. He wrote to his brother at 22: “I have no fear of death. I feel myself above personal misfortune.” At that point he was a minor artillery officer with no prospects. Corsican accent. No connections. No money. Within a decade, he would command the largest army in European history.

Napoleon III had the same feeling. So did countless people history erased. The problem is obvious: the feeling is necessary but not sufficient. It tells you nothing about whether you’re right.

Worse, it might be negatively correlated with self-knowledge. The uncle and the nephew felt identical certainty. One was genius recognizing itself. The other was inheritance mistaken for destiny.

From inside, they’re indistinguishable.

The Red Napoleon

Mikhail Tukhachevsky was called the Red Napoleon by western observers, and he earned the title.

Born in 1893 to minor Russian nobility, he joined the Tsar’s army at 21 and was captured by the Germans within months. He escaped five times. On the fifth attempt, he made it.

He joined the Bolsheviks in 1918 because the Revolution was the only game that matched his ambitions. Within two years, at 27, he commanded an entire front in the Civil War. He crushed the White armies in Siberia. He nearly took Warsaw before his supply lines collapsed.

By 30, he was one of the most powerful military figures in Soviet Russia.

He pioneered “deep battle” doctrine, the theory of mechanized warfare that would later define World War II. He built the Soviet tank corps and air force from scratch. While other generals were still thinking about cavalry charges, he was gaming out how armor and aircraft would transform combined arms operations. He was right about everything. The Wehrmacht would prove it in 1941, using tactics he’d developed a decade earlier.

In 1937, Stalin had him arrested on fabricated charges of conspiracy with Nazi Germany. He was tortured, confessed to crimes he didn’t commit, and was shot within 24 hours. He was 44.

He spent his whole life building the instrument that might have saved the Soviet Union from Germany. Stalin destroyed him, purged the officer corps, and then watched the Wehrmacht use Tukhachevsky’s own tactics to drive to the gates of Moscow.

Three Cases

Napoleon I: the feeling was right. Napoleon III: the feeling was wrong. Tukhachevsky: the feeling was right and it didn’t matter.

The Marxist Problem

Marx had a word for all of this: Bonapartism.

In The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon, he diagnosed Napoleon III: “History repeats itself, first as tragedy, then as farce.” But the critique went deeper. Bonapartism is what happens when class conflict reaches a stalemate. Into the vacuum steps the strongman, someone who appears to transcend faction, to represent the nation itself. The Bonapartist leader seems to bend the system to his will. In reality, he serves it. He provides the illusion of agency while the actual structure remains intact.

Here’s the uncomfortable question: was Napoleon I any different? Was Tukhachevsky?

The Revolution needed someone. It had destroyed the old order and couldn’t stabilize the new one. The Soviet state needed military modernizers. Maybe all “great men” are products of forces they don’t control. The system produces people who feel like protagonists, and the ones who happen to fit the moment get remembered as geniuses.

The Marxist answer is: dissolve the impulse entirely. Accept that history is made by structures and classes, not by individuals who feel special.

This critique has no easy answer. One can gesture at free will, at the irreducibility of individual action, but the Marxist position is difficult to refute. Maybe the whole idea of great men is an illusion, and history is just determinism wearing a mask. The Revolution would have found its general. The Soviet state would have found its modernizer.

And yet people proceed anyway—which might just be the illusion doing its job.

The Counterfactual

In 1793, the siege of Toulon needed an artillery commander. The previous one had been wounded. Napoleon happened to be nearby. He proposed a plan, it worked, and within months he was a general. Without that accident of proximity, he might have remained a minor officer. Competent. Respected. Anonymous.

There’s a version of Napoleon who took a job in the Ministry of Finance because it was stable. Who became a successful banker in Paris and never commanded an army. By any reasonable metric, his life would have been good. But it would have been a life in the wrong arena.

The banker Napoleon never finds out what he actually was.

The Bismarck Problem

Otto von Bismarck was a mediocre law student. A failed bureaucrat. He managed his family’s estates for a decade through his late twenties and early thirties. The “mad Junker,” drinking, dueling, drifting. His mother had wanted him to be a diplomat. He couldn’t hold a government job.

Except he wasn’t drifting. He was reading. He watched the 1848 revolutions sweep through Europe and fail. He studied why. He built a model of power: what actually moved states, how coalitions formed and fractured, where the leverage points were.

When the moment came (a parliament seat, almost by accident) he was ready in a way the credentialed weren’t. Within a decade, he had unified Germany through three precisely calibrated wars.

The estate wasn’t the thing. It was cover for the thing.

From inside, preparation and drift look the same.

The Asymmetry

Tukhachevsky was 44 when he died. In that time he revolutionized military doctrine, commanded armies, shaped the structure of a superpower’s defense. Then a bullet in a basement.

There’s a case to be made: a consequential life cut short beats a long life in the wrong arena.

Closing

Napoleon III’s mistake wasn’t ambition. It was believing the feeling was enough.

Napoleon I had the feeling and the genius and the moment. The uncle got all three. The nephew got one, and assumed the others would follow. Tukhachevsky had all three too. And the system destroyed him anyway.

Every ambitious person faces the same question. The answer only comes in retrospect.

Comments

Loading comments...